|

"He who is possessed of supreme knowledge by

concentration of mind, must have his senses under control, like

spirited steeds controlled by a charioteer." says the Katha

Upanishad (iii, 6). From the Vedic age downwards the

central conception of education of the Indians has been that it

is a source of illumination giving us a correct lead in the

various spheres of life. Knowledge, says one thinker, is the

third eye of man, which gives him insight into all affairs and

teaches him how to act. (Subhishitaratnasandhoha p. 194).

As

per classical Indian tradition “Sa vidya ya vimuktaye”, (that

which liberates us is education).

A single feature of ancient

Indian or Hindu civilization is that it has been molded and

shaped in the course of its history more by religious than by

political, or economic, influences. The fundamental principles

of social, political, and economic life were welded into a

comprehensive theory which is called Religion in Hindu thought.

The total configuration of ideals, practices, and conduct is

called Dharma (Religion, Virtue or Duty) in this ancient

tradition. From the very start, they came, under the influence

of their religious ideas, to conceive of their country as less a

geographical and material than a cultural or a spiritual

possession, and to identify, broadly speaking, the country with

their culture. The Country was their Culture and the Culture

their Country, the true Country of the Spirit, the 'invisible

church of culture' not confined within physical bounds. India

thus was the first country to rise to the conception of an

extra-territorial nationality and naturally became the happy

home of different races, each with its own ethno-psychic

endowment, and each carrying its social reality for Hindus is

not geographical, not ethnic, but a culture-pattern. Country and

patriotism expand, as ideals and ways of life receive

acquiescence. Thus, from the very dawn of its history has this

Country of the Spirit ever expanded in extending circles,

Brahmarshidesa, Brahmavarta, Aryavarta, Bharatvarsha, or

Jambudvipa, Suvarnabhumi and even a Greater India beyond its

geographical boundaries.

Learning in India through the

ages had been prized and pursued not for its own sake, if we may

so put it, but for the sake, and as a part, of religion. (It was

sought as the means of self-realization, as the means to the

highest end of life. viz. Mukti or Emancipation. Ancient

Indian education is also to be understood as being ultimately

the outcome of the Indian theory of knowledge as part of the

corresponding scheme of life and values. The scheme takes full

account of the fact that Life includes Death and the two form

the whole truth. This gives a particular angle of vision, a

sense of perspective and proportion in which the material and

the moral, the physical and spiritual, the perishable and

permanent interests and values of life are clearly defined and

strictly differentiated. Of all the people of the world the

Hindu is the most impressed and affected by the fact of death as

the central fact of life. The individual's supreme duty is thus

to achieve his expansion into the Absolute, his

self-fulfillment, for he is a potential God, a spark of the

Divine. Education must aid in this self-fulfillment, and not in

the acquisition of mere objective knowledge.

Introduction

Rigvedic Education

Education in the Epics

Period of Panini

Buddhist Education

Universities

Professional

and Useful Education

Conclusion

Introduction

It may be said with

quite a good degree of precision that India was the only country

where knowledge was systematized and where provision was made for

its imparting at the highest level in remote times. Whatever the

discipline of learning, whether it was chemistry, medicine,

surgery, the art of painting or sculpture, or dramatics or

principles of literary criticism or mechanics or even dancing,

everything was reduced to a systematic whole for passing it on to

the future generations in a brief and yet detailed manner.

University education on almost modern lines existed in India as

early as 800 B.C. or even earlier. The learning or culture of

ancient India was chiefly the product of her hermitages in the

solitude of the forests. It was not of the cities. The learning of

the forests was embodied in the books specially designated as

Aranyakas "belonging to the forests." Indian

civilization in its early stages had been mainly a rural, sylvan,

and not an urban, civilization.

The ideal of education

has been very grand, noble and high in ancient India. Its aim,

according to Herbert Spencer is the 'training for completeness of

life' and the molding of character of men and women for the battle

of life. The history of the educational institutions in ancient

India shows how old is her cultural history. It points to a long

history. In the early stage it is rural, not urban. British Sanskrit scholar Arthur

Anthony

Macdonell (1854-1930) author of A

History of Sanskrit Literature (Motilal Banarsidass

Pub. ISBN: 8120800354) says "Some hundreds of years

must have been needed for all that is found" in her culture.

The aim of education was at the manifestation of the divinity in

men, it touches the highest point of knowledge. In order to attain

the goal the whole educational method is based on plain living and

high thinking pursued through eternity.

As the

individual is the chief concern and center of this Education,

education also is necessarily individual. It is an intimate

relationship between the teacher and the pupil. The relationship

is inaugurated by a religious ceremony called Upanayana.

It is not like the admission of a pupil to the register of a

school on his payment of the prescribed fee. The spiritual meaning

of Upanayana, and its details inpsired by that meaning, are

elaborated in many texts and explained below in the proper place.

By Upanayana, the teacher, "holding the pupil within him as

in a womb, impregnates him with his spirit, and delivers him in a

new birth." The pupil is then known as Dvija, "born

afresh" in a new existence, "twice

born" (Satapatha Brahmana). The education that is

thus begun is called by the significant term Brahmacharya,

indicating that it is a mode of life, a system of practices.

This conception of

education molds its external form. The pupil must find the

teacher. He must live with him as in member of his family and is

treated by him in every way as his son. The school is a natural

formation, not artificial constituted. It

is the home of the teacher. It is a hermitage, amid sylvan

surrounding, beyond the distractions of urban life, functioning in

solitude and silence. The constant and intimate

association between teacher and taught is vital to education as

conceived in this system. The pupil is imbibe the inward method of

the teacher, the secrets of his efficiency, the spirit of his life

and work, and these things are too subtle to be taught. It

seems in the early Vedic or Upanishadic times education was

esoteric. The word Upanishad itself suggests that it is learning

got by sitting at the feet of the master. The knowledge was to be

got, as the Bhagavad Gita says, by obeisance, by questioning and

serving the teacher.

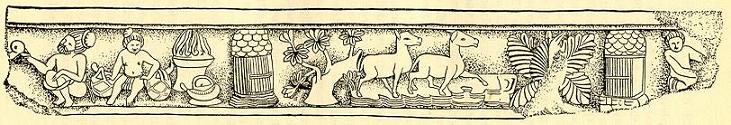

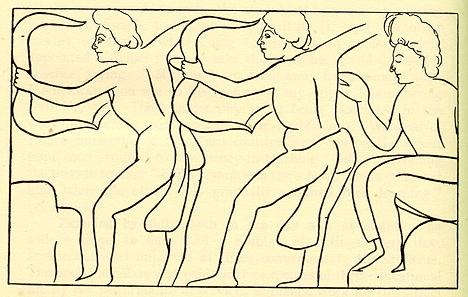

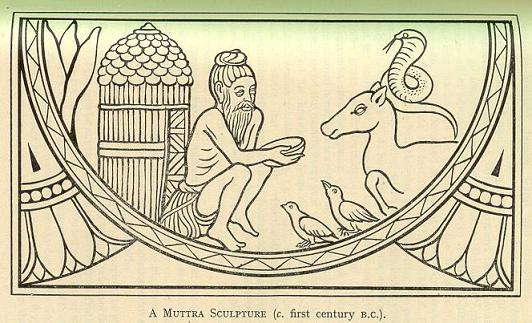

The ascetic, clad in birch bark, with matted hair bound up into a knot,

leaning and grieving over his dead pet antelope.

The inscription:

Dighatapasi sise anusasati, "the ascetic of long penance instructs the

pupils." Some of the pupils are female rishis. The position of the

pupils' fingers show counting called for in Sama Veda chanting.

(image source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

India

has believed in the domestic system in both Industry and

Education, and not in the mechanical methods of large production

in institutions and factories turning out standardized

articles.

It

is these sylvan schools and hermitages that have built up the

thought and civilization of India. As has been pointed out in the

graphic words of the poet and Nobel prize laureate, Rabindranath

Tagore (1861-1941):

"A

most wonderful thing was notice in India is that here the forest,

not the town, is the fountain head of all its civilization.

Wherever in India its earliest and most wonderful manifestations

are noticed, we find that men have not come into such close

contact as to be rolled or fused into a compact mass. There, trees

and plants, rivers and lakes, had ample opportunity to live in

close relationship with men. In these forests, though there was

human society, there was enough of open space, of aloofness; there

was no jostling. Still it rendered it all the brighter. It is the

forest that nurtured the two great ancient ages of India, the

Vaidic and the Buddhist. As did the Vaidic Rishis, Buddha also

showered his teaching in the many woods of India. The current of

civilization that flowed from its forests inundated the whole of

India."

"The

very word 'aranyaka' affixed to some of the ancient treatises,

indicates that they either originated in, or were intended to be

studied in, forests."

(source:

India: Bond Or Free? - By Annie Besant

p. 94-95).

"In

order to preserve the continuity of this national heritage and add

to its richness, India built large institutions of higher learning

from time to time. They served as the repositories of her

spiritual, philosophical, scientific, artistic and literary

achievements and as the media of transmission of this heritage to

the future generations. But it was realized by the early Vedic

seers that the educational institutions could only discharge their

functions properly if they were isolated from the conflicting

demands of the rough and tumble of the world. They, therefore,

built their universities in forests, or in places of natural

beauty. Nature softens the instincts of body and mind, which

otherwise become harsh and aggressive when man lives in houses of

brick and mortar. When man lives in the lap of nature, his

emotional and mental life becomes pure and harmonious; he grows as

a part of life that surrounds him. His inner strains and stresses

are reduced to minimum, his mind is alert, his intuition awake. Ancient

India, therefore, selected spots of natural beauty for locating

its educational institutions."

(source:

India:

A synthesis of cultures – by Kewal Motwani p.

131).

It

is here, in these forest universities, as Sir

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1888-1975) has said, '

evolved the beginning of the sublime idealism of India.'

(source:

Everyday Life in Ancient India -

By

Padmini Sengupta p. 161).

Top

of Page

Rigvedic Education

The

Rig Veda as the source of Hindu Civilization

The

Rig Veda is established as the earliest work not merely of the

Hindus, but of all Indo-European languages and humanity. It

lays the foundation upon which Hindu Civilization has been

building up through the ages. Broadly speaking, it is on a

foundation of plain living and high thinking. Life was simple but

though high and of farthest reach, wandering through eternity.

Some of the prayers of the Rig Veda, like the widely known Gayatri

mantram also found in Samaveda and Yajur veda touch the highest

point of knowledge and sustain human souls to this

day.

The

Rig Veda itself exhibits an evolution and the history of the

Rigveda is a history of the culture of the age. The Rig veda, in

the form in which we have it now, is a compilation out of old

material, a collection and selection of 1,017 hymns out of the

vast literature of hymns which have been accumulating for a long

period. When the Rigvedic texts was thus fixed and appropriated

for purposes of the Samhita, its editors had to think out the

principles on which the hymns could be best arranged. These show

considerable literary skill, originality of design, and insight

into religious needs. First, it represents

Rishis were chosen and their works were utilized to

constitute six different Mandalas. These

Rishis are Gritsamada, Visvamitra, Vamadeva, Atril, Kanva, Bharadvaja,

and Vasistha.

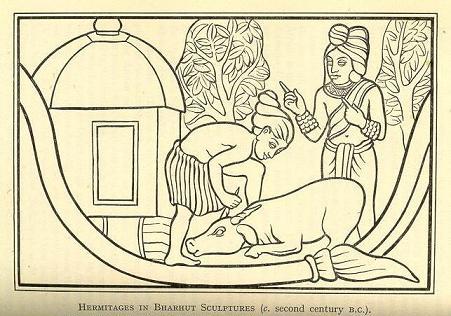

1.

Vasishtha 2. Visvamitra 3. Vamadeva 4. Bharadvaja 5. Atri 6. Kanva 7. Gritsamada

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

When

the highest knowledge was thus built up by these Seers and

revealed and stored up in the hymns, there were necessarily

evolved the methods by which such knowledge could be acquired,

conserved, and transmitted to posterity. Thus every Rishi was a

teacher who would start by imparting to his son the texts of the

knowledge he had personally acquired and such texts would be the

special property of his family. Each such family of Rishis was

thus functioning like a Vedic school admitting pupils for

instruction in the literature or texts in its possession. The

relations between teacher and taught was well established in the

Rig Veda. The methods of education naturally varied with the

capacity of pupils. Self-realization by means of tapas would be

for the few.

The

Rig Veda shows a lively sense of the immutable laws governing

Creation. Its best expression is iii. 56, I, a hymn of

Visvamitra. It means that the Vratas or Cosmic Laws which are at

the root of creation, operate for all time and regularly, which

can never be violated by anyone however clever or wise. There is

no one in earth or heaven who by his power or supreme knowledge

can set them at naught. "They cannot bend like

mountains."

"Then

at the beginning, before creation, there was neither Being nor

non-Being. There was neither the atmosphere nor the heavens

beyond. What did it contain? Where? And under whose direction?

Were there waters, and the bottomless deep?"

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

Commenting on these Vedic hymns Count

Maurice Maseterlinck in is book The

Great Secret

(Citadel Pub ASIN: 0806511559) says:

"Is

it possible to find, in our human annals, words more majestic,

more full of solemn anguish, more august in tone, more devout,

more terrible? Where, from the depths of an agnosticism, which

thousands of years have augmented, can we point to a wider

horizon? At the very outset, it surpasses all that has

been said, and goes farther than we shall even dare to go. No

spectacle could be more absorbing than this struggle of our

forefathers of five to ten thousand years ago with the Unknowable,

the unknowable nature of the causeless Cause of all Causes. But of

this cause, or this God, we should never have known anything, had

He remained self-absorbed, had He never manifested Himself."

Thus it is, say the Laws of Manu, "that, by an alternation of

awakening and repose, the immutable Being causes all this

assemblage of creatures, mobile and immobile, eternally to return

to life and to die." He exhales Himself, or expels His

breath, throughout the Universe, innumerable worlds are born,

multiply and evolve. He Himself inhales, drawing His breath, and

Matter enters into Spirit, which is but an invisible form of

Matter: and the worlds disappear, without perishing, to

reintegrate the Eternal cause, and emerge once more upon the

awakening of Brahma - that is, thousands of millions of years

later; to enter into Him so it has been and ever shall be, through

all eternity, without beginning, without cessation, without

end."

"When the

world had emerged from the darkness," says the Bhagavata

Puranam,

"the subtle elementary principle produced the vegetable seed

which first of all gave life to the plants. From the plants, life

passed into the fantastic creatures which were born of the slime

in the waters; then, through a series of different shapes and

animals, it came to Man." They passed in succession by way of

the plants, the worms, the insects, the serpents, the tortoises,

cattle, and the wild animals - such is the lower stage," says

Manu again, who adds, "Creatures acquired the qualities of

those that preceded them, so that the farther down its position in

the series, the greater its qualities.

"Have we not

here the whole of Darwinian evolution confirmed by geology and

foreseen at least 6,000 years ago?

On the other hand, is this

not the theory of Akasa which we more clumsily call the ether,

the sole source of all substances, to which our science is

returning? Is it true that the recent theories of Einstein deny

ether, supposing that radiant energy - visible light, for

example - is propagated independently through a space that is an

absolute void. But the scientific ether is not precisely the

Hindu Akasa which is much more subtle and immaterial being a

sort of spiritual element or divine energy, space uncreated,

imperishable, and infinite."

(source: Ancient

Indian Education - By Radha Kumud Mookerji

p. 17 and 49).

Women

as Rishis

The

history of the most of the known civilizations show that the

further back we go into antiquity, the more unsatisfactory is

found to be the general position of women. Hindu civilization is

unique in this respect, for here we find a surprising exception to

the general rule. The further back we go, the more satisfactory is

found to be the position of women in more spheres than one; and

the field of education is most noteworthy among them. There

is ample and convincing evidence to show that women were regarded

as perfectly eligible for the privilege of studying the Vedic

literature and performing the sacrifices enjoined in it down to

about 200 B.C. This need not surprise us, for some of the hymns of

the Rig Veda are the composition of twenty sage-poetesses.

Women

were then admitted to fulfill religious rites and consequently to

complete educational facilities. Women-sages were callee Rishikas

and Brahmavadinis. The Rig Veda knows of the following Rishikas

1.Romasa 2.Lopamudra 3.Apala 4. Kadru

5.Visvavara 6. Ghosha 7. Juhu 8. Vagambhrini 9.

Paulomi 10 Jarita 11. Sraddha-Kamayani 12.

Urvasi 12. Sarnga 14. Yami 15. Indrani

18. Savitri 19. Devajami 20. Nodha 21

Akrishtabhasha 22. Sikatanivavari 23. Gaupayana.

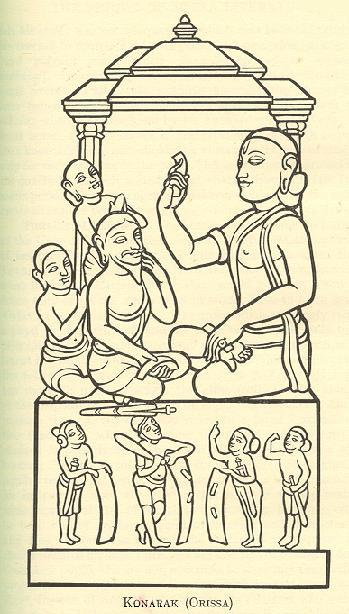

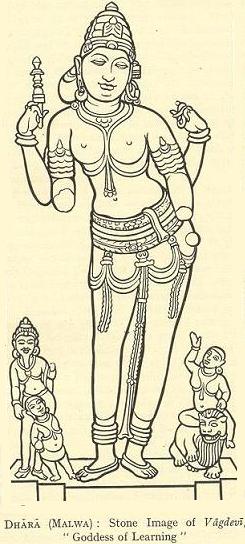

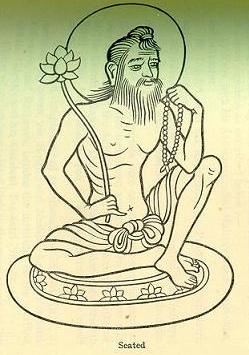

Sculpture

showing Vaishanava Guru and his royal discipline at Konark, holding in his right hand a MS, with his attending guards shown

below.

Now on display at the Victoria Albert Museum in

London, England.

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

The

Brahmavadinis were the products of the educational discipline of

brahmacharaya for which women also were eligible. Rig Veda refers

to young maidens completing their education as brahmacharinis and

then gaining husbands in whom they are merged like rivers in

oceans. Yajurveda similarly states that a daughter, who has

completed her brahmacharya, should be married to one who is

learned like her. A most catholic passage occurs in YajurVeda (xxvi,

2) which enjoins the imparting of Vedic knowledge to all classes,

Brahmins and Rajanyas, Sudras, Anaryas, and charanas (Vaisyas) and

women. No one can recite Vedic prayers or offer Vedic

sacrifices without having undergone the Vedic initiation (Upanayana).

It is, therefore, but natural that in the early period the

Upanayana of girls should have been as common as that of boys. The

Arthava Veda (xi. 5.8) expressly refers to maidens undergoing the

Brahmacharya discipline and the Sutra works of the 5th century

B.C. supply interesting details in its connection. Even Manu

includes Upanayana among the sanskaras (rituals) obligatory for

girls (II.66). Music and dancing was also taught to them.

Brahmavadins used to marry after their education was over, some of

them like Vedavati, a daughter of sage Kusadhvaja, would not marry

at all.

Women

in Education

Radha Kumud Mookerji

(1884 -1964) Indian historian, has noted: "An important

feature of this educational system should not be missed. The part

taken in intellectual life by women like Gargi who could address a

Congress of philosophers on learned topics, or like Maitreyi, who

had achieved the highest knowledge, that of Brahma. The Rigveda

shows us some women as authors of hymns, such as Visvavara, Ghosha,

and Apala."

(source:

Hindu Civilization - By Radha Kumud Mookerji

p. 111 Longmans, Green and Co. London 1936).

The

Vedic women received a fair share of masculine attention in

physical culture and military training. The Rigveda tells us that

many women joined the army in those days. A form of chariot race

was one of the games most popular during the Vedic period. People

were fond of swinging. Ball games were in vogue in those days by

both men and women. Apart from this, a number of courtyard games

like" Hide and seek" and "Run and catch" were

also played by the girls. Playing with dice became a popular

activity. The dices were apparently made of Vibhidaka nuts. From

the Rigveda, it appears that the Vedic Aryans knew the art of

boxing.

Top

of Page

Education in the Epics

Takshashila

was a noted center of learning. The story is told of one of its

teachers named Dhaumya who, had three disciples named Upamanyu,

Aruni, and Veda.

Hermitages

The

Mahabharata tells of numerous hermitages where pupils from

distant parts gathered for instruction round some far-famed

teachers. A full-fledged Asrama is described as consisting of

several Departments which are enumerated as following:

-

Agnisthana,

the place for fire-worship and prayers

-

Brahma-sthana,

the Department of Veda

-

Vishnusthana,

the Department for teaching Raja-Niti, Arthaniti, and Vartta

-

Mahendrasthana,

Military Section

-

Vivasvata-sthana,

Department of Astronomy

-

Somasthana,

Department of Botany

-

Garuda-sthana,

Section dealing with Transport and Conveyances

-

Kartikeya-sthana,

Section teaching military organization, how to form patrols,

battalions, and army.

The

most important of such hermitage was that of the Naimisha,

a forest which was like a university. the presiding personality of

the place was Saunaka, to whom

was applied the designation of Kulapati,

sometimes defined as the preceptor of 10,000 disciples.

The

hermitage of Kanva was another

famous center of learning, of which a full description is given. It

is situated on the banks of the Malini, a tributary of the Sarayu

River. It was not a solitary hermitage, but an assemblage of

numerous hermitages round the central hermitage of Rishi Kanva, the

presiding spirit of the settlement. There were specialists in every

branch of learning cultivated in that age; specialists in each of

the four Vedas; in sacrificial literature and art; Kalpa-Sutras; in

the Chhanda (Metrics), Sabda (Vyakarana), and Nirukta. There were

also Logicians, knowing the principles of Nyaya, and of Dialectics

(the art of establishing propositions, solving doubts, and

ascertaining conclusions). There were also specialists in the

physical sciences and art. There were, for example, experts in the

art of constructing sacrificial altars of various dimensions and

shapes (on the basis of a knowledge of Solid Geometry); those who

had knowledge of the properties of matter (dravyaguna); of physical

processes and their results of causes and their effect; and

zoologists having a special knowledge of monkeys and birds. It was

thus a forest University where the study of every available branch

of learning was cultivated.

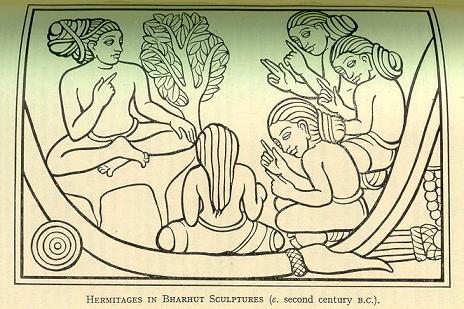

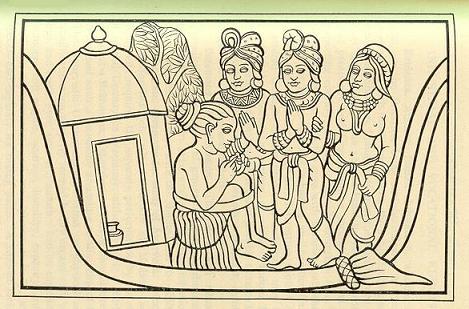

Hermitage

of Rishi Bharadvaja at Prayaga, or at Atri at Chitrakuta; showing

Rama, Lakshmana and Sita standing before the Rishi.

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

The

hermitage of Vyasa was another seat of learning. There Vyasa taught

the Vedas to his disciples. Those disciples were highly blessed

Sumantra, vaisampayana, Jamini of great wisdom, and Paila of great

ascetic merit." They were afterwards joined by Suka, the

famous son of Vyasa.

Among

the other hermitages noticed by the Mahabharata may be mentioned

those of Vasishtha and Visvamitra and that in the forest of

Kamyaka on the banks of the Saraswati. But a hermitage near

Kurkshetra deserves special notice for the interesting fact

recorded that it produced two noted women hermits. There

"leading from youth the vow of brahmacharya, a Brahmin maiden

was crowned with ascetic success and ultimately acquiring yogic

powers, she became a tapassiddha", while another lady, the

daughter not of a Brahmin but a Kshatriya, a child not of poverty

but affluence, the daughter of a king, Sandilya by name, came to

live there the life of celibacy and attained spiritual

pre-eminence.

Top

of Page

Period of Panini

When

we study how these institutions grew we find that students

approached the learned souls for the acquisition of knowledge.

Parents, too encouraged it and sent their boys to the institutions.

When their number began to increase the institutions formed with

these students began to grow gradually. With the lapse of time these

institutions turned into Universities and were maintained with the munificent

gift of the public and the state. In this way many institutions were

formed of which Taxila, Ujjain, Nalanda, Benares, Ballavi, Ajanta,

Madura and Vikramsila were very famous. Taxila was famous for

medicine and Ujjain for Astronomy. Both were pre-Buddhist. Jibaka

the well known medical expert and the state physician of the King of

Magadha of the 6th century B.C. and Panini the famous grammarian of

the 7th century B.C. and Kautilya, the authority on Arthasastra, of

the 4th century B.C. were students of Taxila.

Education

as revealed in the grammatical Sutras of Panini, together with the

works of Katyayana and Patanjali. The account of education in the

Sutra period will not be complete without the consideration of the

evidence of the grammatical literature as represented in the works

of Panini and his two famous commentators, Katyayana and Patanjali.

Panini throws light on the literature of his times. Four classes

of literature are distinguished.

Bhagiratha

in Meditation - Pallava relief of 7-8th century A.D. at Mamallapuram.

The Yogi (who was a king) appears to be petrified by his prolonged

penance and has become a part of the rocks round him. His penance

moves Goddess Ganga who melts and descends from Heaven to Earth,

pouring out Her bounty in streams of plenty.

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

There

is evidence that girls have been admitted in Vedic schools or

Charanas. Panini refers to this specially.

A Kathi is a female student of Katha school. There are hostels for

female students and they are known as Chhatrisala. Each

Charana or school has an inner circle of teachers known as Parisad.

Their decisions on doubts about the reading and the meaning of Vedic

culture are binding. Pratisakyas are said to be the product of such

Parisad.

The

academic year has several terms. Each term is inaugurated by a

ceremony called Upakarnmana and ends by the Utsarga ceremony.

Holidays (Anadhyayas) are regularly observed on two Astamis (eight

day of the moon) two Chaturdasis (fourteenth day of the moon),

Amavasya, Purnima and on the last day of each of the four seasons,

called Chaturmasi. Besides these Nitya (regular) holidays there are

Naimittika (occasional) holidays due to accidental circumstances, eg.

storms, thunder, rain, fog, fire, eclipses etc.

Top

of Page

Buddhist Education

Buddhism

as a phase of Hinduism

Buddhist

education can be rightly regarded as a phase of the ancient Hindu

system of education. Buddhism, itself, especially in its original

and ancient form, is, as has been admitted on all hands, rooted

deeply in the pre-existing Hindu systems of thought and

life.

Max

Muller in Chips from a German

Workshop i 434), "To my mind, having approached

Buddhism after a study of the ancient religion of India, the

religion of the Veda, Buddhism has always seemed to be, to a new

religion, but a natural development of the Indian mind in its

various manifestations, religious, philosophical, social, and

political."

Auguste

Barth

(1834-1916) in The Religions of

India, p. 101 calls Buddhism: "a Hindu phenomenon,

a natural product, so to speak, of the age and social circle that

witnessed its birth", and "when we attempt to

reconstruct its primitive doctrine and early history we come upon

something so akin to what we meet in the most ancient Upanishads

and in the legends of Hinduism that it is not always easy to

determine what features belong peculiarly to it."

T.

W. Rhys

Davids (1843-1922)

in Buddhism

p. 34 calls Gautama Buddha "the creature of his times",

of whose philosophy it must not be supposed that "it was

entirely of his own creation." He wrote: "The fact we

should never forget is that Gautama was born and brought up and

lived and died a Hindu. On the whole, he was regarded by the Hindus

of that time a Hindu. Without the intellectual work of his

predecessors, his work, however, original, would have been

impossible. He was the greatest and wisest and best of the Hindus

and, throughout his career, a characteristic India."

Edward

Washburn Hopkins (1857-1932) goes so far as to assert (The

Religions of

India p. 298) that "the founder of Buddhism did

not strike out a new system of morals; he was not a democrat; he

did not originate a plot to overthrow the Brahminic priesthood; he

did not invent the order of monks."

Hermann

Oldenberg (1854-1920):

"For hundreds of years before Buddha's time, movements were in

progress in Indian thought which prepared the way for

Buddhism."

(source:

Ancient India - By V. D. Mahajan

p. 197).

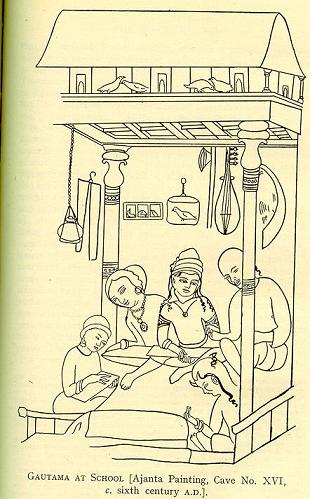

The

school is "in a verandah in his father's palace; Gautama

Buddha being instructed, with three other boys, by a Brahmin

teacher. On their laps are tablets...caged birds, musical

instruments, a battle-axe, bows. Gautama, a prince, was given,

along with literary education, education in music and military

arts like archery.

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

The

Buddha was a product of the Hindu System

The

thesis also receives a most conclusive confirmation from the

details of the Buddha's own career as preserved in the traditional

texts. The details show how largely Buddha

was himself the product of the then prevailing Hindu educational

systems. We see how in the very first step that he

takes towards the Buddhahood, the renunciation of the home and the

world, the world of riches to which he is born, he was not at all

singular but following the path trodden by all seekers after truth

in all ages and ranks of society. Our ancient literature is full

of examples of the spirit of acute, utkata,

vairagya under which the rich, the fortunate, and the

noble not less than the poor, the destitute and the lowly, the

young with a distaste for life before tasting it as much as the

old who have had enough of it, even women and maidens, as eagerly

leave their homes and adopt the ascetic life as a positive good as

their dear ones entreat them to desist such a step. The Buddha's

next step was to place himself under the guidance of two

successive gurus. The first was the Brahmin, Alara

Kalama, at Vesali, having a following of 300 disciples who taught

him the successive stages of meditation and the doctrine of the

Atman, from which the Buddha turns back dissatisfied on the ground

that it "does not lead to aversion, absence of passion,

cessation, quiescence, knowledge, supreme wisdom and Nirvana, but

only as far as the realm of nothingness". Next he attaches

himself to the sage of Rajagaha with 700 pupils, Uddaka, the

disciple of Rama but "he gained no clear understanding from

his treatment of the soul." As Rhys

David points out "Gotama, either during this

period or before must have gone through a very systematic and

continued course of study in all the deepest philosophy of the

time."

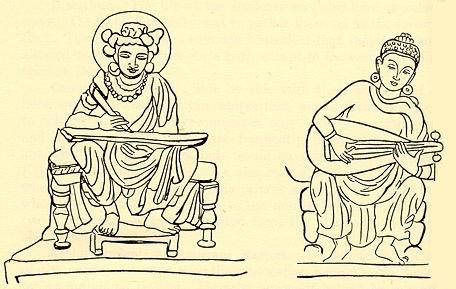

Gautama

at School: practicing writing. Gautama at School: learning

music

Gautama

at school: being instructed in Archery - Gandhara Sculptures

- 2nd century A.D.

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

In the Lalitavistara Sastra,

the education of Buddha as a child, aged eight by the Sage

Vishvamitra, who says:

Let us turn to Numbers. Count after me

Until you reach lakh (= one hundred thousand):

One, two, three, four, up to ten

Then in tens, up to hundreds and thousands,

After which, the child named the numbers,

Then the decades and the centuries, without stopping.

And once he reached lakh, which he whispered in silence,

Then came koti, nahut, ninnahut, khamba,

viskhamba, abab, attata,

Up to kumud, gundhika, and utpala

Ending with pundarika (leading)

Towards paduma, making it possible to count

Up to the last grain of the finest sand

Heaped up in mountainous heights.

(source:

The

Universal History of Numbers - By Georges

Ifrah p. 421 - 423).

Takshasila/Taxila - The Most Ancient University

Takkasila

was the most famous seat of learning of ancient India. Takkasila

was also the capital of Gandhara and its history goes back into hoary

antiquity. It was founded by Bharata and

named after his son Taksha, who was established there as its ruler. Janamejaya's

serpent sacrifice was performed at this very place. As a center

for learning the fame of the city was unrivalled in the 6th century

B.C. Its site carries out the idea held by the ancient Hindus of the

value of natural beauty in the surroundings of a University. The

valley is "a singularly pleasant one, well-watered by a girdle

of hills." The Jatakas tell us of how teachers and students

lived in the university and the discipline imposed on the latter,

sons of Kings and themselves future rulers though they might be!

The Jatakas (No. 252) thinks that this

discipline was likely "to quell their pride and

haughtiness". It

attracted scholars from different and distant parts of India.

Numerous references in the Jatakas show how thither flocked

students from far off Benares, Rajagaha, Mithila, Ujjain, from the

Central region, Kosala, and Kuru kingdoms in the North country.

The fame of Takkasila as a seat of learning was of course due to

that of its teachers. They are always spoken of as being "

world renowned" being "authorities", specialists,

and experts in the subject they professed. Of one such teacher we

read: "Youths of the warrior and brahmin castes came from all

India to be taught the art by him" Sending their sons a

thousand miles away from home bespeaks the great concern felt by

their parents in their proper education. As

shown in the case of the medical student, Jivaka, the course of

study at Takila extended to as many as seven years. Jataka

No. 252 records how parents felt if they could see their sons

return home after graduation at Taxila. One of the archery

schools at Taxila had on its roll call, 103 princes from different

parts of the country. King Prasenajit of Kosala, a contemporary of the

Buddha, was educated in the Gandhara capital. Prince Jivaka, an

illegitimate son of Bimbusara, spent seven years at Taxila in learning

medicine and surgery.

Takshasila

a Center for Higher Education: The

students are always spoken of as going to Takshasila to "complete

their education and not to begin it." They are

invariably sent at the age of sixteen or when they "come of

age".

Different

Courses of Study

"The

Jatakas contain 105 references to Takshasila. "The fame of

Takshasila as a seat of learning was, of course, due to that of

its teachers. They are always spoken of as being 'world-renowned,'

being authorities, specialists and experts in the subjects they

professed. It was the presence of scholars of such acknowledged

excellence and widespread reputation that caused a steady movement

of qualified students from all classes and ranks of society

towards Takshasila from different and distant parts of the Indian

continent, making it the intellectual capital of India of those

days. Thus various centers of learning in the different parts of

the country became affiliated, as it were, to the educational

center or to the central University of Takshasila, which exercised

a kind of intellectual suzerainty over the world of letters in

India." Takshashila was destroyed by the Huns in 455

A.D."

(source:

India:

A synthesis of cultures – by Kewal Motwani

p. 133).

The

Jatakas constantly refer to students coming to Takkasila to

complete their education in the three Vedas and the eighteen

Sippas or Arts. Sometimes the students are referred to as

selecting the study of the Vedas alone or the Arts alone. The

Boddisatta (Buddha) is frequently referred to as having learned

the three Vedas by heart. Takshila

was famous for military training, wrestling, archery and mountain-

climbing.

Science,

Arts and Crafts: The Jatakas mention of subjects under scientific

and technical education. Medicine included a first hand study of

the plants to find out the medicinal ones. Takkasila was also

famous for some of its special schools. One of such schools was

the Medical Schools which must have been the best of its kind in

India. It was also noted for its School of Law which attracted

student from distant Ujjeni. Its Military School were not less

famous, which offered training in Archery. Thus the teachers of

Takkasila were as famous for their knowledge of the arts of peace

as for that of war. Much attention was paid to the

development of social and cultural activities in all possible

ways. Dancing and dramatic groups, singers and musicians and other

artists were given encouragement and offered employment. During

the Sangam epoch in South India, the three principal arts, Music,

Dance and Drama were practiced intensively and extensively

throughout the country, and the epic of Silappadikaram contains

many references to the practice of these arts.

Next,

to Takkasila ranks Benares as

a seat of learning. It was, however, largely the creation of the

ex-students of Takkasila who set up as teachers at Benares, and

carried thither the culture of that cosmopolitan educational

center which was molding the intellectual

life of the whole of India. There were again certain

subjects in the teaching of which Benares seems to have

specialized. There is an expert who was "the chief of his

kind in all India."

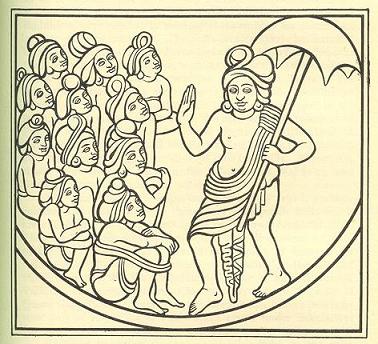

Assembly

of monks seated in three rows and addressed by their leader

standing, with a parasol, in his left hand indicating his rank.

Pre - Gandhara period.

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

Hermitages

as Centers of Highest Learning

Lastly,

it is to be noted that the educational system of the times

produced men of affairs as well as men who renounced the world in

the pursuit of Truth. The life of renunciation indeed claimed many

an ex-student of both Takksila and Benares. In the sylvan and

solitary retreats away from the haunts of men, the hermitages

served as schools of higher philosophical speculation and

religious training where the culture previously acquired would

attain its fruitage.

There

are accounts of education written by eye witness who were

foreigners, like the pilgrims from China who regarded India, as

its Holy Land. The very fact of the

pilgrimage of Chinese scholars like Fa-Hien or Hiuen Tsang to

India testifies to the tribute paid by China to the sovereignty of

Indian thought and culture which made its influence felt beyond

the bounds of India itself in distant countries which might well

be regarded as then constituting a sort of a Greater India. The

duration of Fa-Hien's travel in India was for fifteen years.

"After Fa-Hien set out from Ch'ang-gan it took him six years

to reach Central India; and on his return took him three years to

reach Ts'ing-chow. A profound and abiding regard for the learning

and culture of India was needed to feed and sustain such a long

continued movement. Indeed, the enthusiasm for Indian wisdom was

so intense, the passion for a direct contact with its seats was so

strong, that it defied the physical dangers and difficulties which

lay so amply in the way of its realization. Besides, Chinese

scholars, I-tsing refers to "the Mongolians of the

North" sending students to India.

The

teachers themselves were most exemplary. Hiuen Tsang says of the

Brahmins: "The teachers (of the Vedas) must themselves have

closely studied the deep and secret principles they contain, and

penetrated to their remotest meaning. They then explain their

general sense, and guide their pupils in understanding the words

which are difficult. They urge them on and skillfully conduct

them. They add luster to their poor knowledge and stimulate the

desponding." Studies were pursued unremittingly, and Hiuen

Tsang says: "The day is not sufficient for asking and

answering profound questions. From morning till night they engage

in discussion; the old and the young mutually help one

another."

(source:

Life

of Hiuen-Tsiang

- by Samuel Beal vol. I p. 79 and vol II p. 170).

Attached

to the university was a kind of post-graduate department, a group

of learned Brahmins known collectively as a parishad. A parishad

seems usually to have consisted of ten men; four 'walking

encyclopedias' each of whom had learnt all the four Vedas by

heart, three who had specialized in one of the Sutras, and

representative of the three orders of brahmachari grihastha and

vanaprastha - student, householder and hermit. The parishad gave

decisions on disputed points of religion of learning. I-Tsing

reports that at the end of their course of studies, 'to try the

sharpness of their wit' some men 'proceed to the king's court to

lay down before it the sharp weapon of their abilities: there they

present their schemes and show their talent, seeking to be

appointed in the practical government..."

(source:

Everyday

Life in Ancient India - By Padmini Sengupta p.

162-169).

It

is interesting to note that the study of Sanskrit was continued in

Buddhist monasteries. At the Pataliputra monastery Fa-Hien stayed

for three years "learning Sanskrit books and the Sanskrit

speech and writing out the Vinaya rules." Archery is found

mentioned in the Jataka stories. The Bhimsena Jataka tells that

Boddhisatva learnt archery at Takshila. Wrestling was popular and

descriptions of such breath-holding bouts in wrestling are

available in the Jataka stories. Two kinds of games called Udyana

Krida or garden games and Salila Krida or water sports are also

mentioned. Archery was also

popular among the women during this period, as can be seen from

the Ahicchatra images. Hunting, elephant fighting, Ram fighting,

and Partridge fighting were the other important games of this

period.

Takshashila,

the most ancient Hindu University, was destroyed by the barbarian

White Huns in 455 A.D. Sir John Marshall, Director General of

Archaeology in India, has given a most interesting account, but he

says regretfully,

"The

monuments of Taxila were wantonly and ruthlessly devastated in the

course of the same (fifth) century. This work of destruction is

almost certainly to be attributed to the hordes of barbarian white

Huns, who after the year 455 A.D. swept down into India in ever

increasing numbers carrying sword and fire wherever they went, and

not only possessed themselves of the kingdom of the Kinshans, but

eventually overthrew the great empire of the Guptas. From this

calamity Taxila never again recovered."

(source:

India: Bond Or Free? - By Annie Besant

p. 94-97).

Top

of Page

Universities

of Ancient India

1. Takkasila

- also known as

Taxila - for information on this university, please refer to the above

passages.

2.

Mithila - Mithila,

was a stronghold of Brahminical culture at its best in the time of

the Upanishads, under its famous Philosopher-king

Janaka who used to send our periodical invitations to

learned Brahmins of the Kuru-Panchala country to gather to his court

for purpose of philosophical discussions. Under him Eastern India

was vying with North-Western India in holding the palm of learning.

In those days, the name of the country was not Mithila but Videha. In

the time of the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and Buddhist literature,

Mithila retained the renown of its Vedic days.

Its

subsequent political history is somewhat chequered. When Vijaya Sen

was King of Bengal, Nanyadeva of the Karnataka dynasty was King of

Mithila in A.D. 1097. King Vijaya defeated him but was defeated by

his son Gangadeva who recovered Mithila from him. This Karnataka

Dynasty ruled Mithila for the period c. A.D. 115-1395, followed by

the Kamesvara Dynasty which ruled between c. A.D. 1350-1515. It was

again followed by another dynasty of rulers founded by Mahesvara

Thakkura in the time of Akbar, and this dynasty has continued up to

the present time.

Mithila

as a seat of learning flourished remarkably under these later kings.

The Kamesvara period was made famous in the literary world by the

erudite and versatile scholar, Jagaddhara,

who wrote commentaries on a variety of texts, the Gita,

Devi-mahatmya, Meghaduta, Gita-Govinda, Malati-Madhava, and the

like, and original treatises on Erotics, such as

Rasika-Sarvasva-Sangita-Sarvasva.

The

next scholar who shed luster on Mithila was the poet Vidyapati, the

author of Maithili songs or Padavali generally. He has inspired for

generations the later Vaishava writers of Bengal.

Mithila

made conspicious contributions in the realm of severe and scientific

subjects. It developed a famous School of

Nyaya which flourished from the twelfth to the fifteenth

century A.D. under the great masters of Logic, Gangesa, Vardhamana,

Pakshadhara, and others. This School of New Logic (Navya Nyaya) was

founded by Gangesa Upadhyaya and his

epoch-making work named "Tattva

Chinatmani", a work of about 300 pages whose

commentaries make up over 1,000,000 pages in three centuries of its

study. Gangesa is supposed to have lived after A.D. 1093-1150, the

time of Ananada Suri and Amarachandra Suri, whose opinions he has

quoted.

By its

scholastic activities Mithila in those days, like Nalanda, used to

draw students from different parts of India for advanced and

specialized studies in Nyaya or Logic, of which it was then the

chief center.

3.

Nalanda

Nalanda

was the name of the ancient village identified with modern Baragaon,

7 miles north of Rajgir in Bihar. The earliest mention of the place

is that in the Buddhist scriptures which refer to a Nalanda village

near Rajagriha with a Pavarika Mango Park in Buddha's time. The Jain

texts carry the history earlier than the Buddhist. IT was the place

where Mahavira had met Gosala and was counted as a bahira or suburb

of Rajagriha where Mahavira had spent as many as fourteen rainy

seasons. Nalanda, when Fa-hien visited it, was called Nala and was

known as the place "where Sariputta was born, and to which also

he returned, and attained here his pari-nirvana. Nalanda

was not a sectarian or a religious university in the narrow sense of

the term, imparting only Buddhist thought. Subjects other than

Buddhism were taught as fervently. Almost all sciences, including

the science of medicine were taught. So were the Upanishads

and the Vedas. Panini’s grammar, the science of

pronunciation (Phonetics), etymology, Indology and Yoga were all

included in the curricula. Surprisingly, even archery was taught at

Nalanda. Hiuen Tsang himself learnt Yogasastra from Jayasena.

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

Knowledge

of Sanskrit was essential for all entrants in spite of the fact that

Sakyamuni delivered his sermons in Pali. Knowledge of Sanskrit meant

complete mastery of Sanskrit grammar, literature and correct

pronunciation, and was compulsory to enter the portals of the

university. On the authority of Hiuen Tsang, we can safely say that

the entrants to Nalanda were supposed to be well-versed in "Beda"

i.e. Veda, Vedanta, Samakhya, Nyaya and Vaisesika. I-Tsing also

confirms this in his accounts. Nalanda

was an example of the Guru-Shishya

parampara, a great Indian tradition. The authority of the

Guru (teacher) over the shishya (student) was absolute, and yet,

dissent was permitted in academic matters.Free

education: Out of the income of the estate. In Nalanda, swimming, breathing exercises and yoga

formed an integral part of the curriculum. Harshavardhana, of the

Gupta dynasty was a great sportsman and he encouraged his subjects

as well. Another great contemporary of Harsha, Narasimhan or

Mamallah was also a great wrestler. He belonged to the Pallava

dynasty.

Yuan

Chawang, a Chinese student at Nalanda, wrote: "In the

establishment were some thousand brethren, all men of great

learning and ability, several hundreds being highly esteemed and

famous; the brethren were very strict in observing the precepts

and regulations of their order; learning and discussing, they

found the day too short. Day and night they admonished each other,

juniors and seniors mutually helping to perfection....Hence

foreign students came to the institution to put an end to their

rounds and then become celebrated and those who shared the name of

Nalanda, were all treated with respect, wherever they

went."

(source:

On Yuang-Chwang's Travels in India - By

Thomas Watters (1840-1901) volume 2 p. 165).

Though

Buddhism and Hinduism became arrayed in opposite philosophical

camps, they were both given their places in the university

curriculum. There was no intellectual

isolationism of the type that characterizes modern

sectarian institutions of the Christian world. According to

eminent Indian historian, R C Dutt,

"Buddhism never assumed a hostile attitude towards the parent

religion of India; and the fact that the two religions existed

side by side for long centuries increased their tolerance of each

other. Hindus went to Buddhist monasteries and universities, and

Buddhist learnt from Brahmin sages."

(source:

Civilization in Ancient India - By R C

Dutt p. 127).

According

to Alain Danielou (1907-1994) son of French aristocracy, author of numerous books on philosophy, religion,

history and arts of India: "Hiuen Tsang, the Chinese traveler, stayed

five years at Nalanda University, where more than seven thousand

monks lived. He mentions a very considerable literature in

Sanskrit and other works on history, statistics and geography,

none of which have survived. He also writes of officials whose job

it was to write records of all important events. At Nalanda,

studies included the Vedas, the

Upanishads, cosmology (Sankhya), realist or scientific philosophy

(Vaisheshika), logic (Nyaya), to which great importance was

attached, and Jain and Buddhist philosophy. Studies

also included grammar, mechanics, medicine, and physics. Medicine

was highly effective, and surgery was quite developed. The

pharmacopoeia was enormous, and astronomy was very advanced. The

earth's diameter had been calculated very precisely. In physics,

Brahmagupta had discovered the law of gravity."

(source:

A

Brief History of India - By Alain Danielou p.

165-166).

4.

Vallabi

Valabhi

in Kathiawad was also a great seat of Hindu and Buddhist learning.

It was the capital of an

important kingdom and a port of international trade with numerous

warehouses full of rarest merchandise. During the 7th century,

however, it was more famous as a seat of learning. I-tsing informs

us that its fame rivaled with that of Nalanda in eastern India.

5.

Vikramasila

Like

Nalanda and Vallabhi, the University of Vikramsila was also

the result of royal benefactions. Vikramasila, found by king Dharmapala in the 8th century, was a

famous center of international learning for more than four

centuries. King Dharmapala (c. 775-800 A. D) was its founder, he

built temples and monasteries at the place and liberally endowed

them. He had the Vihara constructed after a good design. He also erected several halls for the lecturing work. His

successors continued to patronize the University down to the 13th

century. The teaching was controlled by a Board of eminent

teachers and it is stated that this Board of Vikramsila also

administered the affairs at Nalanda. The University had six

colleges, each with a staff of the standard strength of 108

teachers, and a Central Hall called the House of Science with its

six gates opening on to the six Colleges. It is also stated that the

outer walls surrounding the whole University was decorated with

artistic works, a portrait in painting of Nagarjuna adorning the

right of the principal entrance and that of Atisa on the left. On

the walls of the University were also the painted portraits of

Pandits eminent for their learning and character.

Grammar,

logic, metaphysics, ritualism were the main subjects specialized

at the institution.

Destruction

of Vikramsila by Moslems: In 1203, the University of Vikramasila

was destroyed by the Mahomadens under Bakhtyar Khilji.

As related by the author of Tabakat-i-Nasari:

"the

greater number of the inhabitants of that place were Brahmins and

the whole of these Brahmins had their heads shaven; and they were

all slain. There were a great number of books on religion of the

Hindus (Buddhists) there; and when all these books came under the

observation of the Musalmans, they summoned a number of Hindus that

they might give them information respecting the import of these

books; but the whole of the Hindus had been killed. On becoming

acquainted (with the contents of those books), it was found that the

whole of that fortress and city was a college, and, in the Hindu

tongue, they call a college a Bihar (Vihara)."

After

the destruction of the Vikramsila University, Sri Bhadra repaired to

the University of Jagadala whence he proceeded to Tibet, accompanied

by many other monks who settled down there as preachers of

Buddhism.

6.

Jagaddala

Its

foundation by King Rama Pala. According to the historical Epic

Ramacharita, King Ram Pala, of Bengal and Magadha, who reigned

between A.D. 108-1130, founded a new city which he called Ramavati

on the banks of the rivers Ganga and Karatoya in Varendra and

equipped the city with a Vihara called Jagadala. The University

could barely work for a hundred years, till the time of Moslem

invasion sweeping it away in A.D. 1203. But in its short life it has

made substantial contributions to learning through its scholars who

made it famous by their writings.

7.

Odantapuri

Very

little is known of this University, although at the time of

Abhayakaragupta there were 1,000 monks in residence here.

Odanatapuri is now known for the famous scholar named Prabhakara who

hailed from Chatarpur in Bengal. It appears that this University had

existed long before the Pala kings came into power in Magadha. These

kings expanded the University by endowing it with a good Library of

Brahmanical and Buddhist works. This Monastery was taken as the

model on which the first Tibetan Buddhist Monastery was built in 749

A.D. under King Khri-sron-deu-tsan on the advice of his guru,

Santarakshita.

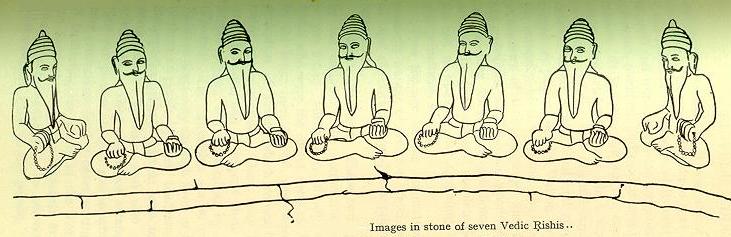

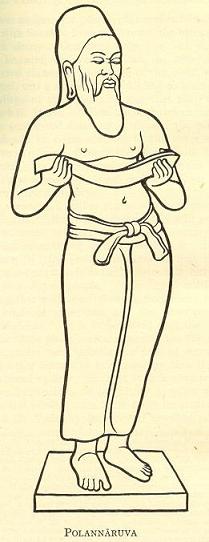

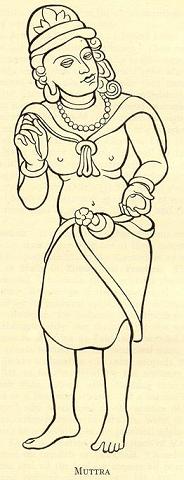

A

typical Brahmin with a high chignon, beard, short garments, seat of

mat, round leafy hut; four fellow denizens of his hermitage, a dow,

a crow, a kneeling doe, and a coiled snake, all living at peace as

friends in the atmosphere of non-violence.

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

8.

Nadia

Nadia

is the popular name of Navadvipa on the Bhagirathi at its confluence

with Jalangi. Once it was a center of trade borne by the Bhagirathi

between Saptframa )on the river Sarasvati near Hoogly) and the

United Provinces, and in the other direction by the Jalangi between

Saptagrama and Eastern Bengal.

9. Madura

Sangham - was another seat of learning. The Sangham

was known for its learning and academic prestige. Writing about the

Tamil institutions, Dr. Krishnaswami

Aiyangar (1871-1947) remarks: "There are two

features with regard to these assemblies that call for special

remark. The first, the academics were standing bodies of the most

eminent men among the learned men of the time in all branches of

knowledge. The next, it was the approval of this learned body that

set the seal of authority on the works preserved to it."

Scholars were honored irrespective of sex. Aiyangar continues:

"A Ruler of Tanjore, poet, musician, warrior, and

administrator, did extraordinary honor to a lady of Court, by name Ramachandramha,

who composed an epic on the achievements of her patron, Raghunatha

Nayaka of Tanjore. It appears that she was accorded honor of Kanaka-Ratna

Abhisheka (bath in gold and gems). She was, by assent of

the Court, made to occupy the position of "Emperor of

Learning."

(source:

India: A synthesis of Culture - By Kewal

Motwani p. 138).

10. Benares -

Benares

has always been a culture center of all India fame and

even in the Buddha's day it was already old. Though not a formal

university, it is a place unique in India, which has throughout the

ages provided the most suitable atmosphere for the pursuit of higher

studies. The method of instruction as also the curriculum followed

there in early times was adopted from Taxila. Benares

University was famous for Hindu culture. Sankaracharya as a student

was acquainted with this university. Benares is the only city in

India which has its schools representing every branch of Hindu

thought. And there is no spiritual path which has not its center in

Benares with resident adherents. Every religious sect of the Hindus

has its pilgrimage there. In ancient days, Sarnath figured as a

recognized seat of Buddhist learning. Rightly, therefore, it is this

holy city the very heart of spiritual India. Alberuni,

the noted Arabian historian, mentioned Benares as a great

seat of learning and Bernier,

who visited India, described it "as a kind of university, but

it resembled rather the school of ancients, the masters being

spread over different parts of the town in private houses."

11. Kachipuram

was another such institution of learning in South India. It came

to be known as Dakshina Kasi, Southern Kashi. Huien Tsang visited

it about 642. A.D. and found Vaishnavite and Shaivite Hindus,

Digambara Jain and Mahayan Buddhists studying together.

12.

Navadvip belonged to

comparatively recent times and was founded by Sena Kings of Bengal

in about 1063 A.D. and soon rose to be a great center of learning.

It imparted instruction in Vedas, Vedangas, Six Systems especially

Nyaya. Chaitanya was a product of Navadvipa. It had 500-600

students, when A. H Wilson visited it in 1821, drawn from Bengal,

Assam, Nepal and South India.

In

1867, Edward B Cowell

(1826-1903) professor of Sanskrit in Cambridge and author of The

aphorisms of Sandilya or The Hindu doctrine of faith,

recorded his opinion in these words: "I could not help looking

at these unpretending lecture-halls with a deep interest, as I

thought of the pundits lecturing there to generation after

generation of eager, inquisitive minds. Seated on the floor with his

'corona' of listening pupils round him, the

teacher expiates on those refinements of infinitesmal logic which

makes a European's brain dizzy to think of, but whose labyrinth a

trained Nadia student will thread with unfaltering precision."

(source:

India: A synthesis of Culture - By Kewal

Motwani p. 134-145 and Indian Education

in Ancient and Later Times - By Key p.145).

Libraries in Ancient India

The great seats of learning in ancient India like Nalanda,

Vikramasila, Pataliputra, and Tamralipti are said to have

contained libraries of their own and striven hard for the

promotion of education and learning in the country, the evidence

for which comes from the writings of Hieun-Tsang and It-Sing who

spent some time in some of the centers and studied the Buddhist

philosophy. They were given all facilities to copy down the

manuscripts which they wanted from the libraries. Each of these

institutions must have maintained a well equipped library for the

use of teachers and students. The library in ancient times was

called either Saraswati-bhandara or Pustaka bhandara. Many

libraries were located in temples. In South India, records contain

references to Nagai, Srirangam, Sermadevi and Cidambaram,

Kacipuram and Sringeri. In this connection it may be mentioned

that libraries in ancient Cambodia were all located in temples and

the inscriptions from some temples in the area bear evidence to

that. Library is mentioned for the first time in the inscriptions

of the king Indravarman at Preah Ko and Bakong

(Cambodia). They were rectangular with gabled ends and at

first with a single vaulted hall. The

temples of Prasat Bantay Pir Chan, and Angkor Wat contained

libraries in which the main deity of the temples were oriented. It

is also interesting to note that the walls of the library were

sculptured with panels depicting scenes from the epics, the

Ramayana and Mahabharata.

"India

has lost much of its great treasures of ancient texts during the

successive invasions by foreign rulers. Our great

libraries at Nalanda and other places were burnt to ashes. Sachan

who collected and edited Al Beruni's

works said: "It was like a magic island of quiet and

impartial research, in the midst of a world of clashing swords,

burning towns, and plundered temples. The work of many eminent

scholars contained thousands of volumes of translations of Indian

texts, whose original were lost in India owing to the depredations

of Mohammedan iconoclasts who destroyed hundreds of Hindu and

Buddhist seats of learning, in India including the world famous

Nalanda University." "The Christian missionaries in the

West coast took away and burnt many valuable manuscripts. Many

great scholars died without passing down their knowledge to the

descendents. In their quest for livelihood during the nine hundred

years of foreign rule, the descendents did not care to preserve

their knowledge."

(source:

Hindu Superiority - Har Bilas Sarda

p. 150 and Vision of India - By Sisir

Kumar Mitra p. 186 and The

Temple Empire - By Vidyavisarada Garimella Veeraraghuvulu.

Printed in Sri Gayathri press. Kakinada. India 1982 p. 136-137)..

***

(Note:

The fall of Nalanda at the hands of the Turks is a story too deep

for tears. Like Nero, Bakhtiar Khilji, its destroyer in 1205 A.D.,

laughed while Nalanda burnt. The City of Knowledge, which took

several centuries to build, took only a few hours to be destroyed.

Legend has it that when some monks fell at the feet of the invader

to spare at least its world-famed library, Ratnabodhi, he

kicked them and had them thrown in the fire along with the books.

The monks fled to foreign lands, citizens became denizens and

Nalanda was relegated to a memory.

(source: Nalanda

- The

City of Knowledge).

Many of these universities

were sacked, plundered, looted by the Islamic onslaught. They destroyed

temples and libraries and indulged in most heinous type of vandalism.

These

were particularly heinous crimes. The burning of the Library of Nalanda ranks

with the destruction of the Library of Alexandria as the two most notorious acts

of vandalism in the course of Islamic expansion. Nalanda,

Vikramshila, Odantapura, and Jagddala as the universities destroyed by Mohammed Bakhtiar

Khilji around 1200 A.D. For more refer to The

Sack of Nalanda).

Gertrude

Emerson Sen ( -

1982) historian and

journalist and Asia specialist, wrote on the plight of the

universities: "Night was to descend on all the great centers of

traditional Indian learning, however, when the untutored Muslims of

Central Asia poured into India with fire and sword at the beginning

of the 11th century."

(source

The

Pageant of India's History - By Gertrude Emerson Sen

p. 275 - 276).

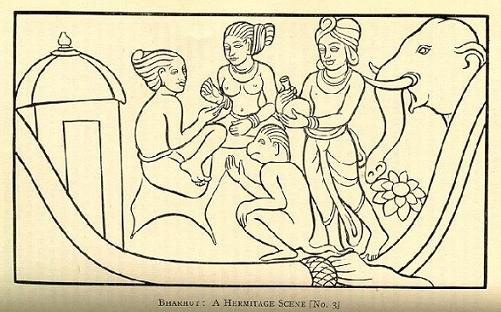

Hermitage

scene

(image

source: Ancient Indian Education - By Radha Kumud

Mookerji).

***

Arrival

of the British in India

Later when

the British came there was, throughout India, a system of communal schools,

managed by the village communities. The agents of the East India Company

and the Christian missionaries destroyed these village

community schools, and took steps to replace education by

introducing English and western system of education. In

October 1931 Mahatma Gandhi made a statement

at Chatham House, London, that created a furor in the English press.

He said,

"Today India is

more illiterate than it was fifty or a hundred years ago, and so is Burma,

because the British administrators, when they came to India, instead of taking

hold of things as they were, began to root them out. They scratched the soil

and left the root exposed and the beautiful tree perished".

Mr. Ermest Havell

(formerly Principal of the Calcutta school of Art) has rightly said,

the fault of the Anglo-Indian Educational System is that, instead of

harmonizing with, and supplementing, national culture, it is

antagonist to, and destructive, of it.

Sir George Birdwood says

of the system that it “has destroyed in Indians the love of their

own literature, the quickening soul of a people, and their delight

in their own arts, and worst of all their repose in their own

traditional and national religion, has disgusted them with their own

homes, their parents, and their sisters, their very wives, and

brought discontent into every family so far as its baneful

influences have reached."

(source:

Bharata Shakti: Collection of Addresses on

Indian Culture - By Sir John Woodroffe p 75-77).

As Max

Mueller, the propagator of the Aryan invasion theory,

wrote to his wife, "It took only 200

years for us to Christianise the whole of Africa, but even after

400 years India eludes us, I have come to realize that it is

Sanskrit which has enabled India to do so. And to break it I have

decided to learn Sanskrit." The soul of India lies in

Sanskrit. And Lord Macaulay saw to it that the later generations

are successfully cut off from their roots.

(source: Assaulting

India's pluralist ethos

- by D. Harikumar The Hindu).

Tremendous harm done by

Colonist history education of India

Colonial

construction of its history denied India both learning and unlearning

experience. The colonists’ version of India’s past harmed its present and

threatened its future.

Take a glaring instance, the Aryan-Dravidian theory constructed by the

colonialists that virtually split India racially and regionally, almost

fomenting a huge secessionist movement in the South.

A society should not get obsessed with its past just for pride. Nevertheless it

becomes inevitable for colonised societies to review the colonialist version of

its history that demeans its faith, philosophy, forefathers, traditions and

economy, and pervades the society’s academic, intellectual and public

discourse.

After an in-depth study,

Kaisa Illmonen

of University

of Turku in

Finland

writes:

“Post colonial subjects will be imprisoned in their colonial history unless they

can find or figure out their own place in history. History must be retold and

rewritten in such a way that a person excluded from the records of the Western

history can still have knowledge of his or her own past.” This not just about

the history of identity. A society’s economic history is critical in a world

that is increasingly driven by global economic agenda.

The Indian people ought to know whether they have a history of worshipping

poverty as the colonialists had made their elites believe or do they have a

tradition of building prosperity. Modern Western history has universalised the

perception that prosperity building was the preserve of the West. The rest of

the world, particularly Asia, including China and India, was ever steeped in

poverty — almost claiming that colonialists had actually improved their lot!

(source:

Indian history is relevant, even for economists – By S. Gurumurthy).

Modern Indian education is

inherently perverse

The current system of education --

allegedly 'modern' -- is inherently perverse: It was imposed upon India by the

British imperialists, with the single-minded purpose of creating coolies and

clerks to help them run the country. That their system was meant to

perpetuate colonialism is demonstrated in the book Masks

of Conquest by

Columbia's Gauri Viswanathan: indeed, English itself was a mask of conquest --

an inferior language thrust upon conquered nations: First India, then Ireland.

The system has succeeded beyond the

wildest dreams of Thomas Babington Macaulay's infamous Minute

on Indian Education,

which wanted to produce little brown sepoys to be the cannon-fodder of Empire,

metaphorically speaking. Such

Brown Sahibs -- deracinated,

laughable imitations of their white masters -- still rule the roost. You merely

have to turn on Indian television to see these people strut about flaunting

awful 'convent accents' and an utter lack of comprehension about what the world

is all about, other than pre-digested nonsense about ye olde Englande or

America.

These 'beautiful people' have

internalised utterly moronic ideas about distribution without ever worrying

about production, quality, or excellence. Which is precisely the reason why

Indian education has, after Independence, produced nothing whatsoever -- yes,

absolutely nothing -- of global calibre. Not one

earth-shaking discovery or invention, not one outstanding theoretical insight!

That this is much worse than under

the imperialists -- in their days, there were world-class discoveries and

inventions coming out of India, by C V Raman, J C Bose

and Srinivasa Ramanujan to name

just three -- should be reason for the education establishment to hang its head

in shame.

In an

earlier time, before the imperialists damaged the system, Indian education was

far more balanced; and no wonder ancient India was the most creative and

innovative civilisation in the world. There was an efflorescence of creative

activity, unmatched even by the Western gold standard: Their Renaissance.

Out of this came things as diverse as

Panini's grammar, the infinite series of

Madhava; the Aryabhatiya,

the Hortus

Malabaricus,

and the

Yogasutras.

In his landmark work, The

Beautiful Tree,

Dharampal has quoted the imperialists

themselves about the quality and quantity of indigenous education. There was a

school in every village, and all groups enjoyed the benefits of gurukula-style

education that created citizens, not drones. That high-quality, individualised

system has been abandoned for today's education factories churning out

ill-prepared, ill-equipped, second-rate graduates.

(source:

Rethinking education in India – By Rajeev Srinivasan

- rediff.com).

Dalits

and Indigenous System of Educaiton

Dharampal

(The Beautiful Tree) has effectively

debunked the myth that Dalits had no place in the indigenous

system of education. Sir Thomas Munro, Governor of

Madras, ordered a mammoth survey in June 1822, whereby the

district collectors furnished the caste-wise division of students

in four categories, viz., Brahmins, Vysyas (Vaishyas), Shoodras (Shudras)

and other castes (broadly the modern scheduled castes). While the

percentages of the different castes varied in each district, the

results were revealing to the extent that they showed an

impressive presence of the so-called lower castes in the school

system.

Thus, in Vizagapatam, Brahmins and Vaishyas together accounted for

47% of the students, Shudras comprised 21% and the other castes

(scheduled) were 20%; the remaining 12% were Muslims. In

Tinnevelly, Brahmins were 21.8% of the total number of students,

Shudras were 31.2% and other castes 38.4% (by no means a low

figure). In South Arcot, Shudras and other castes together

comprised more than 84% of the students!

In the realm of higher education as well, there were regional

variations. Brahmins appear to have dominated in the Andhra and